The "Secretary Problem" is one of the most famous problems in optimal stopping theory. Also known as the marriage problem or the best-choice problem, it asks: How do you maximize your chances of selecting the best candidate when you must make decisions sequentially without the ability to go back?

While the problem was originally framed around selecting a secretary (hence the name), it has fascinating applications to hiring in tech—and equally important limitations that every hiring manager should understand.

The Problem Setup

Imagine you're hiring for a role and you have n candidates to interview. The rules are:

- Sequential evaluation: You must interview candidates one at a time in random order

- Immediate decisions: After each interview, you must either accept or reject that candidate

- No going back: Once you reject someone, you can't hire them later

- Goal: Maximize the probability of selecting the best candidate

If you accept too early, you might miss better candidates later. If you wait too long, the best candidate might already be rejected. What's the optimal strategy?

The Optimal Solution: The 37% Rule

The mathematical solution is elegant: Interview and reject the first 37% of candidates (approximately 1/e, where e is Euler's number ≈ 2.718), then select the first candidate who is better than all previous candidates.

This strategy gives you approximately a 37% chance of selecting the best candidate—which sounds low, but is actually optimal when you can't go back. As n grows large, the probability converges to 1/e ≈ 0.368.

Why 37%?

The mathematics behind this result involves optimizing the probability function. The key insight is that you need to balance:

- Exploration: Seeing enough candidates to establish a baseline

- Exploitation: Acting on that baseline before running out of options

The 1/e fraction emerges naturally from this optimization. For smaller pools, the optimal percentage varies slightly, but 37% is the asymptotic limit.

Applying It to Real Hiring

Let's say you're interviewing 10 candidates for a software engineering role. The 37% rule suggests:

- Interview and reject the first 3-4 candidates (37% of 10)

- Note the best candidate from this "look-see" phase

- Hire the first candidate from the remaining 6-7 who is better than your best from phase one

Here's a Python implementation to demonstrate:

import random

from typing import List, Callable

def secretary_problem_hiring(

candidates: List[float], # Candidate quality scores

look_see_percentage: float = 0.37

) -> dict:

"""

Simulate the secretary problem strategy for hiring.

Args:

candidates: List of candidate quality scores (higher is better)

look_see_percentage: Fraction of candidates to interview before setting threshold

Returns:

Dictionary with selection details

"""

n = len(candidates)

look_see_count = int(n * look_see_percentage)

# Phase 1: Look-see phase - find the best candidate

look_see_candidates = candidates[:look_see_count]

if not look_see_candidates:

return {"selected": None, "error": "Need at least one candidate for look-see"}

threshold = max(look_see_candidates)

# Phase 2: Select first candidate better than threshold

for i in range(look_see_count, n):

if candidates[i] > threshold:

return {

"selected_index": i,

"selected_score": candidates[i],

"threshold": threshold,

"best_score": max(candidates),

"is_best": candidates[i] == max(candidates)

}

# If no one beats the threshold, select the last candidate

return {

"selected_index": n - 1,

"selected_score": candidates[-1],

"threshold": threshold,

"best_score": max(candidates),

"is_best": candidates[-1] == max(candidates)

}

# Example: Simulate 1000 hiring processes with 10 candidates

def simulate_hiring(num_simulations=1000, num_candidates=10):

successes = 0

for _ in range(num_simulations):

# Random candidate quality scores

candidates = [random.random() for _ in range(num_candidates)]

result = secretary_problem_hiring(candidates)

if result.get("is_best"):

successes += 1

success_rate = successes / num_simulations

print(f"Success rate over {num_simulations} simulations: {success_rate:.2%}")

print(f"Expected (theoretical): ~37%")

return success_rate

# Run simulation

simulate_hiring()

Limitations in Practice

While the mathematics is sound, real-world hiring rarely matches the problem's assumptions:

1. No Going Back

In reality, you can often make offers to candidates you previously interviewed, especially if you maintain relationships. The "no going back" constraint is usually artificial.

2. Perfect Information

The problem assumes you can perfectly rank candidates. In practice, candidate evaluation is subjective, noisy, and multi-dimensional. Is the "better" engineer the one with stronger algorithms knowledge, better communication skills, or better cultural fit?

3. Candidate Availability

Real candidates have timelines. They may accept other offers while you're still in your "look-see" phase, breaking the assumption that all candidates are equally available.

4. Multiple Roles

If you're hiring for multiple positions, the strategy changes completely. You might want to batch candidates and make multiple offers.

5. Team Dynamics

Hiring is rarely a solo decision. Team fit, diversity considerations, and collective judgment complicate the simple optimization.

When the Math Helps

Despite its limitations, the Secretary Problem offers valuable insights:

Establishing Baselines

The "look-see" phase concept is useful. Interviewing a few candidates before making offers helps calibrate:

- What does "good" look like for this role?

- How competitive is the candidate pool?

- What's the market rate and availability?

Avoiding Premature Decisions

The math validates a common intuition: don't hire the first acceptable candidate. Even if you don't follow the exact 37% rule, the principle of establishing a threshold before making offers is sound.

Managing Time Pressure

When facing pressure to hire quickly, the Secretary Problem suggests: "If you must hire from n candidates, spending 37% of your time on exploration maximizes your chances of success." This can help push back against unrealistic timelines.

Practical Adaptation

A more practical approach might be:

- Batch initial interviews: Interview 3-5 candidates first to establish your baseline

- Set clear evaluation criteria: Make the threshold objective, not just "better than the last"

- Maintain relationships: Keep strong candidates in your pipeline even if you don't hire them immediately

- Iterate on the role: Use early interviews to refine the job description and requirements

The Broader Lesson

The Secretary Problem teaches us that optimal strategies exist, but they depend on specific constraints. When those constraints don't match reality, blind application of the math can be counterproductive.

In software engineering, we face similar situations. Design patterns, architectural principles, and best practices are mathematical or logical constructs. They're powerful when applied appropriately, but dangerous when treated as dogma without considering context.

Conclusion

The Secretary Problem is a beautiful piece of mathematics that offers insights into hiring—but it's not a hiring playbook. Use it to:

- Understand the value of exploration before exploitation

- Justify time spent on calibration

- Recognize when constraints don't match assumptions

But don't let the math override judgment about team fit, diversity, candidate timelines, or the nuanced reality of finding great engineers. The best hiring strategies combine mathematical insights with human wisdom.

After all, we're not optimizing a function—we're building teams.

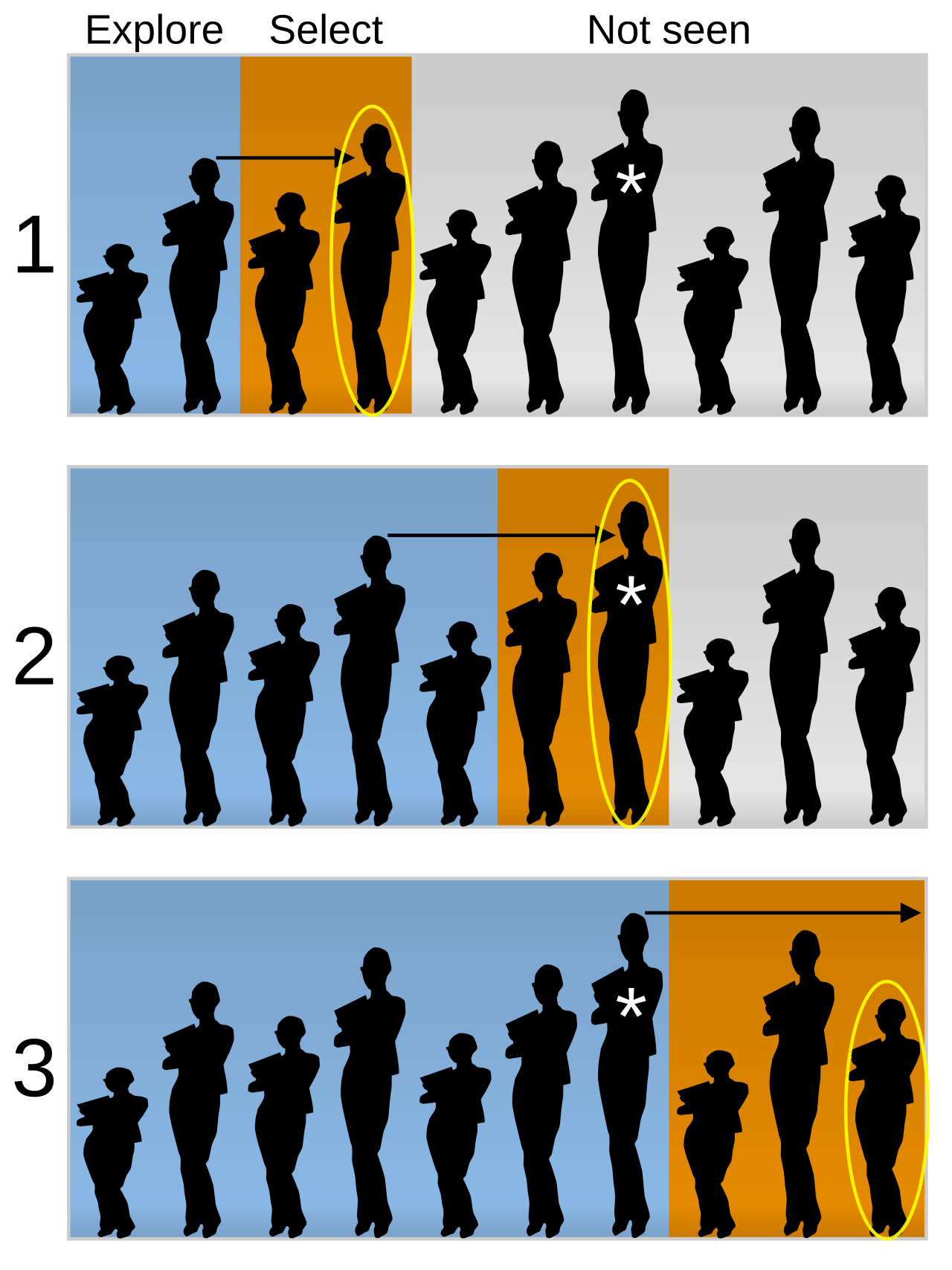

Interactive Visualization

See the 37% rule in action. Each simulation shows how the algorithm selects from 10 candidates.